BART’s 50th Anniversary: The Prototypes That Started It All

The original BART (San Francisco Bay Area Rapid Transit District) car could have had a very different appearance.

Sundberg-Ferar, the industrial design firm that created the original car’s concept and design, recently unearthed a cache of photographs from the 1960s depicting BART in its early stages. There are numerous snapshots of early BART prototypes among the images, some of which we’ve included in this story.

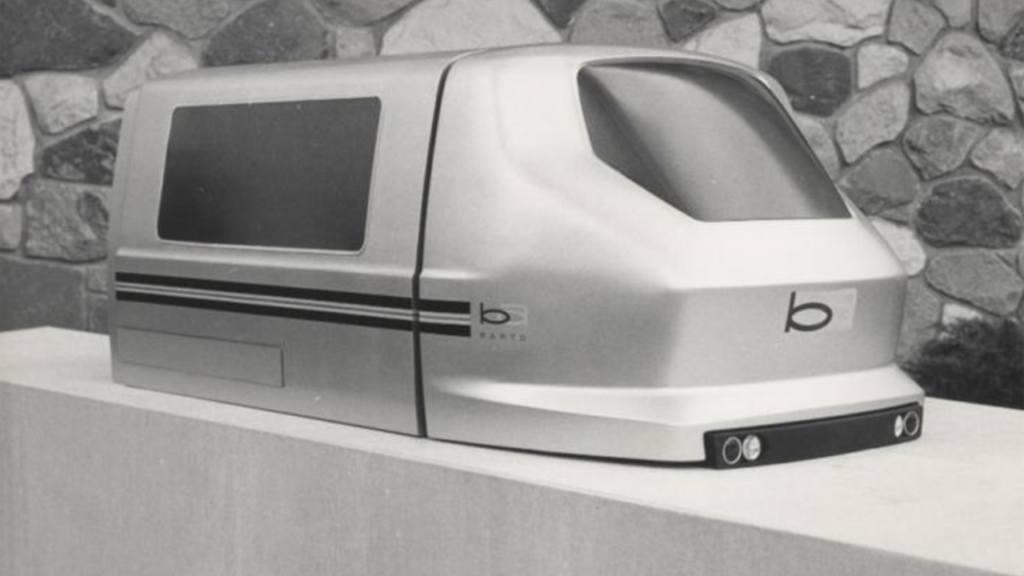

An image of a 1/12 scale model of a 1960s BART railcar prototype. (Image by Sundberg-Ferar, courtesy of BART)

An image of a 1/12 scale model of a 1960s BART railcar prototype. (Image by Sundberg-Ferar, courtesy of BART)

An image of a 1/12 scale model of a 1960s BART railcar prototype. (Image by Sundberg-Ferar, courtesy of BART)

An image of a 1/12 scale model of a 1960s BART railcar prototype. (Image by Sundberg-Ferar, courtesy of BART)

An image of a 1/12 scale model of a 1960s BART railcar prototype. (Image by Sundberg-Ferar, courtesy of BART)

An image of a 1/12 scale model of a 1960s BART railcar prototype. (Image by Sundberg-Ferar, courtesy of BART)

“Prototypes are a low-cost, low-risk way to test design ideas,” Sundberg-Ferar Marketing Manager Lynnaea Haggard explained. “They’re the creation of artifacts for stakeholders to react to, which aids in determining what works and what doesn’t.”

In the early 1960s, BART hired Sundberg-Ferar to design cars for its fledgling mass rail system. By 1964, the company had taken off, beginning with basic concept sketches. Sundberg-Ferar then built a series of 1/12th scale car prototypes. To put that in context, the first prototypes were about 5 3/4 feet long—pint-sized in comparison to the actual cars, which were 70 feet long.

It’s worth briefly returning to the sketching stage. Many of the original BART car concepts were created by acclaimed visionary designer Syd Mead, who is responsible for the look and feel of science fiction classics like “Star Trek,” “Blade Runner,” and “Tron.”

“I was involved in the original design of the BART train cars.” “The BART system cars were designed by Sundberg-Ferar,” Mead said in a 2015 interview before his death in 2019. “I did all of the renderings for the presentation.”

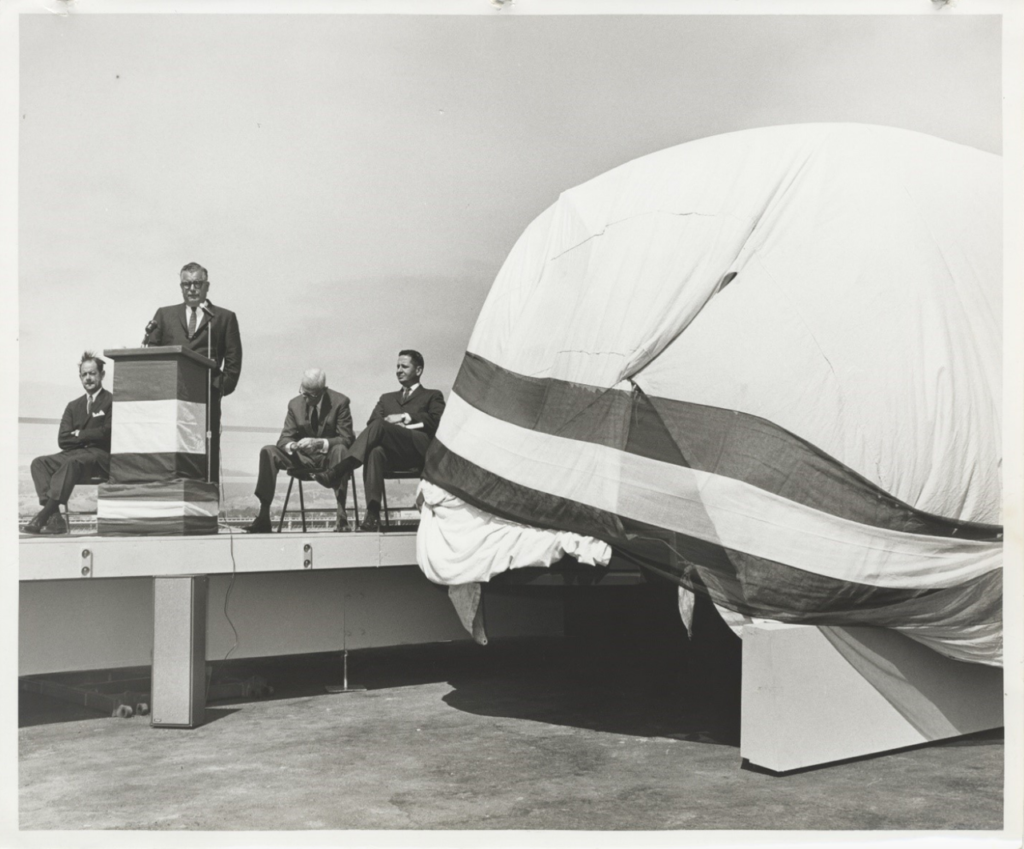

Full-scale prototype construction. (Photo by Sundberg-Ferar, courtesy of BART)

During the interview, Mead revealed that the initial plan was to have a spare cab at each end of each line “so that when the train went across the Bay and then it came back, you wouldn’t have to change the whole train around.” You could remove the control cabin from the back, install another one in front, and then drive away.”

That never happened because “it’s such an elaborate thing,” according to Mead.

Sundberg-Ferar began building a variety of small prototypes with wood after the sketch phase, using a natural metal finish on the outside to further refine and evaluate the design direction. The company then built quarter-scale models and, eventually, a full-scale prototype, which was delivered to California on the back of not one, but two trailers (Sundberg-Ferar was based in Detroit). That model was officially unveiled in June 1965 at BART’s Hayward Test Track, about seven years before the system went into service.

Representatives speak at the June 1965 unveiling of the BART car prototype. (Photo by Sundberg-Ferar, courtesy of BART)

The full-scale model was transported around the Bay Area, with BART allowing members of the public to walk through and experience the sensation for themselves.

“The vehicle experience was mission critical to adoption,” Haggard said.

According to BART historian Michael Healy’s book, “BART: The Dramatic History of the Bay Area Rapid Transit System,” “visitors to the models were, for the most part, very impressed with the cushioned seats, carpeted floors, and clean, wide body.” According to Healy, some people compared the experience to “being on an airplane, only with picture windows.”

“The banner flag was new standards of attractiveness, efficiency, and comfort,” Haggard explained. She stated that one of BART’s design considerations for the project was to make the railcars as comfortable, well-lit, temperature-controlled, and quiet as possible on the tracks.

In 1965, half of the final BART car prototype was transported to California on a trailer. (Photo by Sundberg-Ferar, courtesy of BART)

Carl Sundberg, one of Sundberg-co-founders, Ferar’s was directly involved in the prototype’s development. His goal is to create a people’s railcar.

“This was not going to be some fancy new train,” Haggard explained. “Even though BART was implementing all of these new technologies, that didn’t mean the car would look like a spaceship.”

Sundberg, in fact, wanted the BART car to look like something other than a relic of space travel. “We are not going to the moon or across the country,” he is quoted as saying. It does not have to resemble a projectile.”

As a result, Sundberg didn’t want the public to expect anything streamlined, hence the cab’s iconic sloping nose.

“It had to be a genuine design,” Haggard explained. “A rapid transit vehicle should have the appearance of a rapid transit vehicle.”

Haggard called the project “a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity” for Sundberg-Ferar designers, who had the opportunity to build a mass railcar from the ground up with plenty of creative freedom on BART’s end. BART was the first mass urban rail transit system built in the United States since the early twentieth century at the time—the New York City Subway, for example, opened in 1904.

Above all, Sundberg desired to create railcars with people in mind. Though human-centered design is now widely accepted, it was revolutionary at the turn of the century.

“It must be remembered that the object being worked on will be ridden in, sat upon, looked at, talked into, activated, operated, or in some other way used by people individually or in groups,” industrial designer Henry Dreyfuss wrote in November 1950. “The designer has failed if the point of contact between the product and people becomes a source of friction.” If, on the other hand, contact with the product makes people safer, more comfortable, more likely to purchase, more efficient, or simply happier, then the designer has succeeded.”

Sundberg set out to apply human-centered design theory to the BART car, with voices like Dreyfuss painting a backdrop of design thought.

“This is truly the beginning of an era,” Haggard said. “BART is an incredible representation of a massive mindset shift in mass transit.”